The Shawnee Silver Mines of Kentucky

At Alexandria, Virginia, a British sailor called John Swift wrote in his diary about a treasure they found.

Swift and his companions mined silver until 1769. But they had trouble with the Shawnee to the point that numerous tons of it had to be buried nearby.

Swift and Mundy marked the location of their burial in September 1769 by carving their names and the names of the rest of their company on “…a great beech tree.” According to resources, they also buried “between 22 and 30 thousand English crowns.” During the time, an English crown weighed one ounce of silver. According to one version of the narrative, Swift traveled back to England and was soon imprisoned for expressing his opinions in favor of the insurgent locals of Boston and Williamsburg. So, he was behind bars throughout the Revolution. However, when he came back to America, he was almost completely blind. His notebook and a memory-based map were the only things he left behind, yet he was unable to find the mines.

Lost Treasures Around The World; The Shawnee Silver Mines of Kentucky

One issue with depending on John Swift’s journals is that there are several of them and they are all unique. Jonathan Swift was another that surfaced. While the narrative has similarities in certain areas, such as the burying of enormous sums of silver in various locations, others are entirely distinct and make no reference to George Mundy. Also, the diary claims that the silver was made into Spanish and English coins before being taken to the Appalachian highlands in kegs, where they were buried or stashed away in caverns. The transfer of the silver and later coinage was facilitated by Swift’s occupation as a sailor.

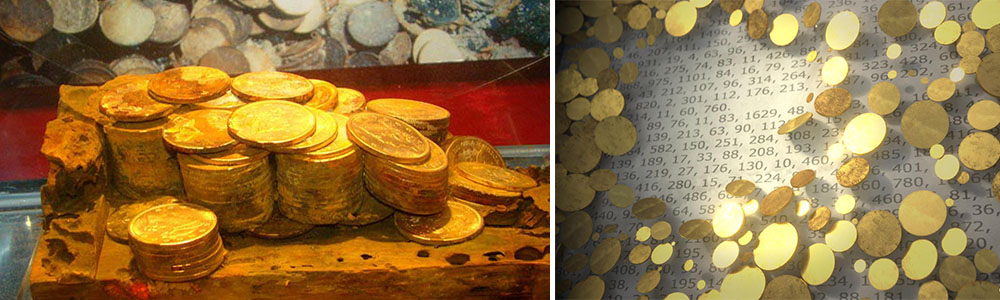

Old Coins

However, Coins dating before 1769 continue to come up in the area. And Swift’s mines have been looked for in Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, and even Pennsylvania, even though the story and others have drawn ridicule from doubters. Many coins, all of which before 1760, were discovered in the late 1980s. They were in a cavern in eastern Kentucky. On the cave wall was a sculpture of a cornstalk. According to Swift’s version, Mundy had initially been brought to the cave as a Shawnee prisoner by Shawnee Chief Cornstalk to be employed as a carrier for the mined silver.

Lost Treasures Around The World; The Shawnee Silver Mines of Kentucky

During a reconnaissance of the area in the 1850s, there were also rumors about the discovery of furnaces for the smelting of silver. There wasn’t much information about the furnaces other than the survey’s comment that they were “old.” Some people searching for Swift’s mine have found nearby stones. Also the initials JS was etched into them as well as other mysterious markings that appear to be hundreds of years old. It’s interesting to note that Jonathan Swift was found guilty of forging English coins in Alexandria in the late 1700s. That created counterfeits that were purer and contained more silver than the real thing. Nobody knows where he acquired the silver from.

Kidd’s Treasure

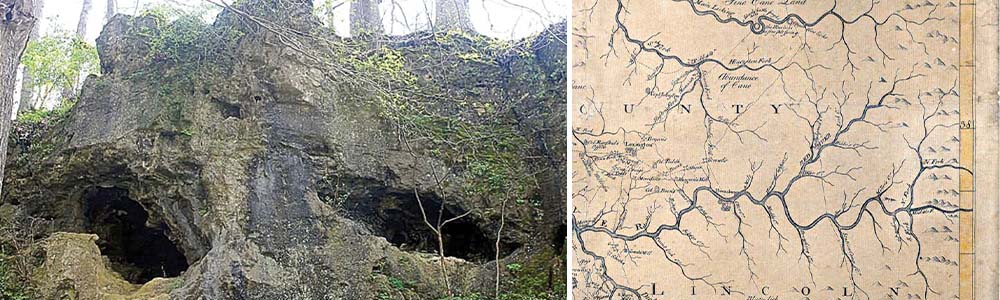

William Kidd, often known as Captain William Kidd or just Captain Kidd, was a Scottish sea captain. He served as a privateer and had previous experience as a pirate. For murder and piracy, he was tried in London in 1701 and put to death.

In Kidd’s case, the French ship that Kidd had taken as a prize was under the command of an English captain. While it was true that the Crown had appointed him as a privateer for this trip, the political climate in England went against him during this case even though he had been appointed as a privateer by the Crown. Several contemporary historians, like Sir Cornelius Neale Dalton, believed his reputation as a pirate was unfair. Also, he asserted that he was operating as a privateer.

Lost Treasures Around The World; Kidd’s Treasure

The idea that Kidd had hidden treasure played a significant role in the development of his reputation. “Two hundred bars of gold, and dollars tenfold, we grabbed unrestrained,” reads the broadside ballad.

Additionally, it served as inspiration for several treasure hunts. The Rahway River in New Jersey was also suspected of having treasure buried in the Rahway River by Kidd. Staten Island’s Arthur Kill can be found across the Arthur Kill from this place.

Mrs. Mercy

On Gardiners Island, off the shore of Long Island, New York, at a location known as Cherry Tree Field, Captain Kidd did hide a small stash of treasure. It was purportedly located and transferred to England by Governor Bellomont. So, Kidd might use it against him in court.

On his visit to Block Island in the 1690s, Kidd was given food by Mrs. Mercy (Sands) Raymond. She was a mariner’s daughter named James Sands. In recompense for her hospitality, it was rumored that Kidd asked Mrs. Raymond to hold out her apron before leaving. He then stuffed it with money and jewelry. After the death of her husband Joshua Raymond, Mercy moved to northern New London, Connecticut, with her family.

Lost Treasures Around The World; Kidd’s Treasure

There, she bought a lot of lands. Family friends claimed that the Raymond family had been “enriched by the apron.” Searches for wealth reportedly buried by Kidd while a privateer began on Grand Manan in the Bay of Fundy as early as 1875 on the island’s west side. This secluded region of the island has been referred to as “Money Cove” for about 200 years.

In 1983, Cork Graham and Richard Knight combed the shoreline of the Vietnamese island of Phu Quc in search of Captain Kidd’s buried riches. Knight and Graham were arrested. Also, they were found guilty of entering Vietnamese territory without authorization. Moreover, each was given a $10,000 fine. They were incarcerated for 11 months before making the fine payment.

Did divers find this treasure in Madagascar?

However, according to BBC news, underwater researchers in Madagascar have reportedly claimed to have found loot that belonged to the infamous Scottish pirate William Kidd from the 17th century. According to the report, a 50kg (7st 9lb) silver bar was hauled to shore on the island of Sainte Marie. Here is where the Adventure Galley is supposed to have sunk. At a formal ceremony, the bar was given to the president of Madagascar. American adventurer Barry Clifford said he thinks the wreck still has a large number of these bars.

Lost Treasures Around The World; Did divers find this treasure in Madagascar?

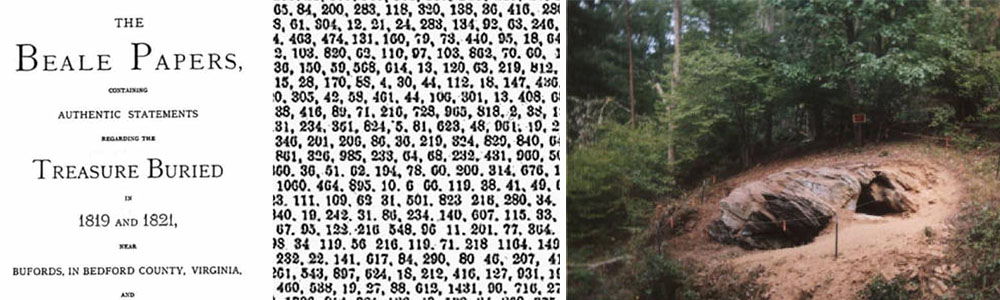

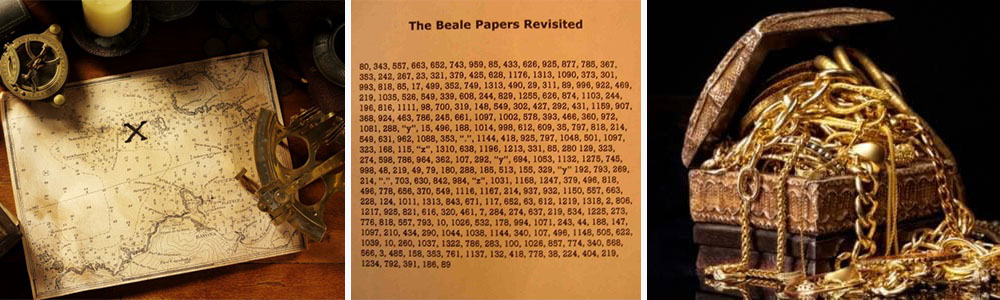

The Beale ciphers

There is a hidden treasure worth more than $60 million somewhere in the lush Bedford County hills of southwest Virginia. The Beale Treasure of gold, silver, and diamonds has been beneath the earth for two centuries. Also, is named for Thomas J. Beale, who is thought to have secretly buried the cache. A three-page secret code known as the Beale Ciphers is the sole indication of where it could be.

More backstory about this purported treasure may be found in Beale’s letter. Thirty young, wealthy men left Virginia in 1817 in search of adventure in the West. They traveled to St. Louis. Then they prepared for a buffalo and bear hunt there. They recruited experts who provided them with guidance on how to organize themselves into a military force. Beale was chosen as their leader.

Lost Treasures Around The World; The Beale ciphers

After that, the company continued to Santa Fe, where they spent the winter. Several of the young guys came into a gold vein while out hunting buffalo a few hundred kilometers north of Santa Fe. The following two years were spent digging up the gold and some silver.

They decided to send the wealth back to Virginia with Beale to be hidden in a cave close to Buford’s Tavern in Buford. Because they were in a hazardous area. Beale buried half the loot when he initially got to Lynchburg. But not in the cave, which was used by farmers for storage. He hid the remaining loot in the same location when he showed up at the Washington Hotel in January 1822.

Letter and the Ciphers

In this letter, Beale informed Morriss that the package included papers that would determine several men’s prospects. Three of the documents needed a key to be deciphered since they were written in cipher. There was a promise that Beale made to a friend in St. Louis that, should he never return to Lynchburg, the friend would send an envelope with the information necessary to decipher the ciphers to Lynchburg in 1832, should he never return. If Beale was never heard from again, he instructed Morriss to open the box on that particular year.

Lost Treasures Around The World; Letter and the Ciphers

Beale vanished. Morriss periodically considered the box. But he didn’t get around to opening the lock until 1845 since the ciphers’ key was never delivered. Three sets of completely illegible papers with precisely written numbers were present in the box. It also contained a letter that Beale wrote in January 1822, not long after arriving back in Lynchburg.

Morriss’s effort

Robert Morriss tried to understand cryptograms for countless hours throughout his life. But was unsuccessful. He transferred the responsibility to an unnamed young man in 1862. Next year, Morriss passed away. The following 23 years were devoted to this unnamed man’s quest to decipher the Beale Ciphers’ codes. He eventually managed to open one of the three using the key. The Declaration of Independence held the key.

Lost Treasures Around The World; Morriss’s effort